Music & Class Status

Mozart’s librettist for The Marriage of Figaro was Lorenzo Da Ponte. This was their first collaboration (of three), and it’s often said that Mozart and Da Ponte were the Dream Team of opera. Da Ponte adapted Beaumarchais’s 1784 play La folle journée, ou le Mariage de Figaro into a tight, clever libretto. But since Da Ponte was well aware that Beaumarchais had gotten into hot water over his politically charged play, he was careful to avoid any potentially inciting scenes and lines in his libretto. Instead, this controversial content played out in Mozart’s music.

In the Classical era (as we now know it) of opera, it was conventional for the noble and upper class characters to sing a recitativo accompagnato, or accompanied recitative, before their major aria. Recitativo accompagnato is recitative that is accompanied by the full orchestra, not just the harpsichord and basso continuo (usually played by the cello). It gives the impression that the singer is commanding the response of the orchestra or vice versa – very much a dialogue

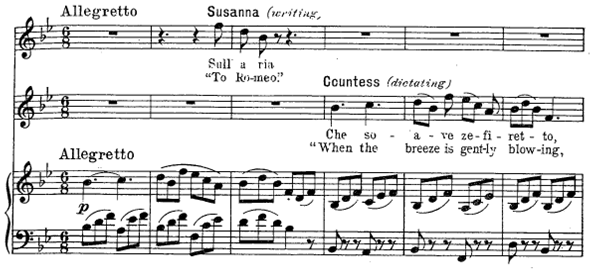

Another convention that Mozart broke is through his use of rustic meters in unexpected contexts. Rhythmic meter in music is the organization of music into regularly recurring measures or bars of stressed and unstressed "beats.” “Rustic” meters were those that had the feeling of triplets, like 6/8. They were to be used exclusively for lower class characters in certain situations, like peasant dances or shepherds singing, for example. Possibly to put his two heroines on more equal footing, Mozart uses the 6/8 meter in the famous duet between Susanna and the Countess, “Sull’aria”…“Che soave zeffiretto,” when they are writing a letter together to deceive the Count.

It may be one of the most beautiful and serene-sounding duets of all time, yet it is in the meter of a lower class.

Mozart does this again in Susanna’s aria “Deh vieni non tardar” near the end of the opera. After singing her “noble” accompanied recitative, Susanna sings a beautiful aria about anticipating love – set in a rustic meter while she is dressed as the Countess. Conversely, Figaro’s aria “Se vuol ballare” in Act 1 is set to a noble dance meter, the courtly minuet in 3/4.

Check out the 2014 Opera Insider for the rest of Emily's article, as well as history on the productions and what inspired the composers and librettists to write them, interviews with the artists, conversation-starting questions and activities….even a musical version of Sudoku!

Figaro sings the words “If he wants to dance, my dear little Count, I’ll play the guitar for him, indeed.” The fact that a servant sings these impertinent words to a noble dance meter clearly turns the tables on who is in control in this lower class/upper class relationship. These kinds of musical nuances may be lost on today’s audiences, but they were certainly pushing boundaries in Mozart’s time.

Check out the 2014 Opera Insider for the rest of Emily's article, as well as history on the productions and what inspired the composers and librettists to write them, interviews with the artists, conversation-starting questions and activities….even a musical version of Sudoku!

No comments:

Post a Comment